In this in-depth story, Timothy Paulson, Arrive Ministries’ Immigration Counselor introduces us to the story of a Somali man, Musa, who Arrive Ministries resettled, assisted in applying for his green card, and helped him and his family become U.S. citizens.

In this in-depth story, Timothy Paulson, Arrive Ministries’ Immigration Counselor introduces us to the story of a Somali man, Musa, who Arrive Ministries resettled, assisted in applying for his green card, and helped him and his family become U.S. citizens.

This story is a rare look into Musa’s life story from his difficult childhood due to extreme tribalism in his homeland of Somalia, to finding himself separated from his family as a person with refugee status in Thailand, to his harrowing journey to the United States, as well as his hopes for this nation.

I arrived at Safari Restaurant on Lake Street, and sat down across the table from a man who has experienced the kind of things I have only read about in books or seen in movies.

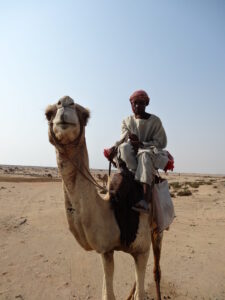

Stock Image of Camel Herder

The man’s name is Musa, and as he settled into the booth across from me, he caught the server’s attention to order some Somali tea. Before I started the interview in earnest, we talked for a bit about our families and the weather. Musa gladly introduced me to the restaurant servers and staff whom he knew well. Then, once we had our tea, I began to ask him some questions about his life and the circumstances that had formed him and brought him here.

I had to take care of our family’s camels from a young age. I would spend up to one year by myself with the camels from the time that I was 11 years old. “I was always someone who was accountable,” Musa began. “I had to take care of our family’s camels from a young age. I would spend up to one year by myself with the camels from the time that I was 11 years old.”

I shook my head in disbelief, when I was eleven years old, my biggest responsibilities were mowing the lawn and walking the dog. In fact, I loathed mowing the lawn since it meant dodging hills of fire ants in the Florida heat, although it is more likely that I simply preferred to sit inside and play video games instead of working. My immediate impression of Musa was that we not only grew up in completely different cultures, but that he could have taught my eleven year-old self a thing or two about work.

Musa went on to explain that he came from a family of pastoralists, raising camel herds and driving them hundreds of miles across the desert in search of water during dry seasons. The key time to search for water was when the mother camels were expecting their young. It was no short commitment, since camels have one of the longest gestational periods of any mammal, anywhere from 13 to 16 months.

Stock Image of Camel Herder

“There is a certain time of the year that the camels usually become pregnant,” said Musa. “I had to take them across the desert, we had to follow the rain.” Musa’s father would keep on the lookout for weather systems that promised rain, and he trained Musa as his apprentice in guiding the camels across the barren desert, chasing after the water-laden clouds.

“There weren’t any cell phones then,” Musa said with a smile. “My father would meet me about once a month. If I was sick or bitten by a snake, I was all done,” he said with a clap of his hands. Musa also explained that his father would help him find a “home base” in particularly promising areas, where Musa could return with the camels at night so they could sleep in a position of relative safety.

Musa faced many hazards as a pre-teen camel driver. “Hyenas and lions were the worst. But I never faced a lion like my father did when he was young.”

(Hyenas) will follow you for days. They look into your eyes, and they just want you to be afraid. They try to scare you or to make you run away, which is when they will attack. You have to be brave. “So, what about the hyenas?” I asked. “What was it like to have them around?”

Musa shook his head. “They will follow you for days. They look into your eyes, and they just want you to be afraid. They try to scare you or to make you run away, which is when they will attack. You have to be brave.”

I considered for a moment how brave I would have been around hyenas in the desert as an adolescent, and then queried aloud what he would do if there were more than one hyena. “Climb a tree,” he replied with a grin.

Musa grew up herding anywhere between fifteen and thirty camels, tracking down the wanderers and keeping the young safe from predators. Musa showed me a video of a young camel herder being interviewed in Somalia who was the same age Musa had been when he started driving camels. “This boy, he is tougher than any boy you meet today in America. He is strong.”

Musa was strong too, but he also had dreams.

He dreamed to one day leave behind the life of a camel driver and attain higher education and eventually to start a business of his own.

“My father passed away in the civil war in 2003.” Musa stared at his tea as he thought back to that time. “We moved to Mogadishu [the capital city of Somalia]; I wanted to start a different life.”

I was trying to have knowledge that would give me opportunities to open up the possibilities.After a pause, Musa continued. “I had this life of driving camels and caring for a farm, and it was difficult. I had a dream to go to school and to learn how to support myself. I wanted to transform myself from a camel driver to someone else. I went to a private school, and I focused on learning English, math, and Arabic. I went on to high school for those things too. Then I went to college – my wife’s father helped me apply for a scholarship to go to college. At college I majored in accounting and studied business management. I was trying to have knowledge that would give me opportunities to open up the possibilities.”

Musa married young, at 20 years old. Then, at age 21, he was suddenly faced with the prospect of leaving his homeland forever.

Somali culture is largely based on tribal tradition and structure. There are a handful of major clans with dozens of sub-clans and smaller minority clans. Just after he was married, a man from a different tribe formed a personal vendetta against Musa and promised to kill him.

As an American, I was pretty unfamiliar with the working of clan culture. Sure, you might have your Packers and Vikings fans who occasionally duke it out in a parking lot, but that doesn’t quite seem to capture the essence of clan identity.

Stock Image of Camel Herder

When I asked what it was like to grow up with these kinds of tribal divisions, a look of aversion come over his face. “When it comes to tribalism, people forget even their ethics and their religion! Someone from one of these big tribes was causing problems for me; it was very difficult, and my life was in danger. This person wanted to kill me and actually made attempts on my life.”

Musa knew that he could not hope to live with his family in peace if some things did not change, and yet he was not willing to resort to retaliation against the man who had made him an enemy. “But leaving the country is not an easy decision to make. My wife was even pregnant when I decided that I must go.” Despite the threat to his own life, Musa knew his wife would be safe living with his mother and other family members since the man only wanted to kill Musa. Yet, if he hoped to have a future with his family, Musa had to leave and seek safety somewhere else.

From that point of decision, his path to the United States was a long and difficult journey.

Musa gave me some context for how his journey began. “At that time in Somalia, there were people who came back from other countries, and they would convince everyone that they could help a poor family from Somalia to leave. They convinced people that they could trust them, that they could provide transport to another country.”

The family saved money to buy Musa’s way to safety; Musa’s mother even contacted family members in Canada to request money. They used these funds to contract one of the smugglers to deliver Musa out of danger. “So, these smugglers promised to take me to London. My wife stayed with her family and planned to join me once I got stabilized there.” Musa planned to claim asylum in England based on the threat to his life, hoping to start a new life there with his wife and growing family.

“So, these guys booked me on a plane, and we were supposed to go through Qatar and on to England. One of these smugglers was going to go with me the whole way.”

The smuggler provided documents that would at least let them land in London, where Musa would then claim asylum immediately. After Qatar, the man was still with Musa on the plane and when they landed at their next destination, the smuggler took him immediately to a hotel in the dead of night. Musa knew he had to lie low and follow the directions of the man who had brought him this far. “It was dark, and he found me a hotel room. I didn’t recognize anything. The next morning, I came out of the hotel room, and the man was gone.” The smuggler had disappeared, and Musa knew immediately that he had not woken up in London.

He was in Bangkok, Thailand. He was 3,800 miles from home, and he was all alone.

Musa had just awoken to find himself alone in Thailand. The deal he had struck with the smuggler was to be transported to England, where Musa would file for asylum and then bring his family to join him. Instead, the man whom he had contracted to take him to London dumped Musa at a cheap hotel in Bangkok and left him to fend for himself.

“I sat for a long time at a table at the hotel, waiting to see if the man would come back,” Musa said. The man never returned.

I had nothing. I could not speak the language. Life was hard and scary. I had a hundred dollars, and it was gone right away. “Here in America you have a cell phone, you have a hospital you can find, or you can go to a restaurant and ask for food. There, I had nothing. I could not speak the language. Life was hard and scary. I had a hundred dollars, and it was gone right away,” he said with a snap of his fingers.

It must have been much cheaper for the smuggler to buy tickets to Thailand instead of England. Apparently, the entire plan had been to cheat Musa out of the money he and his family had painstakingly collected to secure his safety.

It must have been much cheaper for the smuggler to buy tickets to Thailand instead of England. Apparently, the entire plan had been to cheat Musa out of the money he and his family had painstakingly collected to secure his safety.

Musa wandered around Bangkok searching for anyone who spoke a language he could recognize. “It was like life and death. I did not have a phone or anyone I could call. I could not communicate with anyone that I knew to ask for help.” Eventually, he ran into some people from Ghana, a country in West Africa. They spoke English, so he asked if they knew any Somalis. Thankfully, they gave Musa directions to a restaurant owned by a man from his homeland.

“This Somali man took me to his apartment and he helped me a lot. He let me have a place to live, food to eat. He showed me where the UN [United Nations] office was, and how to apply there for refugee status. I saw all these other refugees like me from all these countries, and that was when my life in Thailand began.”

The United Nations has programs in many countries for registering and assisting people who are refugees from their countries of origin. They facilitate the process for people who qualify as they seek to resettle in a third country, especially focusing on the most vulnerable ones who have no hope of returning to their homelands. So, Musa began the long waiting process as he sought to adjust to life in Thailand.

“I was there about one year before I was able to bring my wife and daughter to join me. Refugees are not allowed to work in Thailand; at any minute, I could be arrested. I had one friend who spent three years in jail just waiting for some kind of relief.”

…when you are in survival mode, you don’t think about what is possible or impossible, you think of what you need in the moment to live. Having heard the stories of other immigrants who have sought survival in countries that restrict movement and employment, I knew that this was not usual. Even so, I wondered aloud how Musa survived in a place where he did not speak the language and where it was illegal for him to work.

“First, God helped me a lot,” he responded. “Also, when you are in survival mode, you don’t think about what is possible or impossible, you think of what you need in the moment to live. I asked how I could adapt.” Musa told me his knowledge of English helped, because he got some work with a local organization that partnered with the UN to help refugees. They provided medical assistance, education, food, and other forms of help to refugees. Musa was paid a stipend of about $160 per month to do interpretation work. When I asked him how much he paid in rent, he smiled and said, “More than $160.”

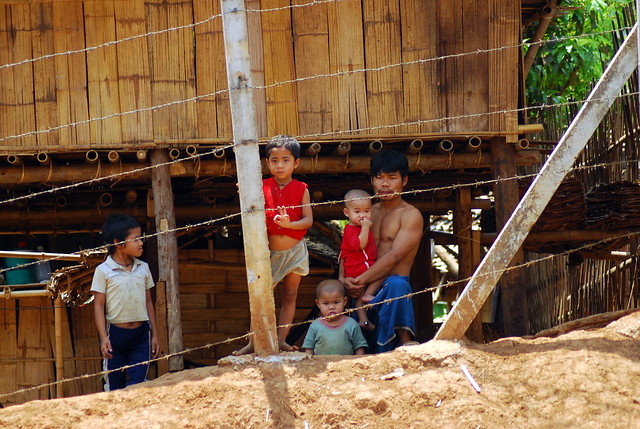

Stock Photo of Thailand Refugee Camp

I shook my head as I thought about Musa’s predicament. Here, one might relocate or add a second job to make ends meet, but as an unwelcome refugee in Thailand, Musa didn’t have the luxury of such options. I asked the obvious question: “Well, how did you make ends meet?”

“You have to be smart and good with people,” he said with a shrug.

It turned out that Musa’s resourcefulness led him to make an important personal connection; he found a Somali friend who “knew a guy.” This guy was a certain Father Dan, an American priest and psychologist who assessed refugee candidates for psychological trauma or related issues that might require treatment.

“I would just interpret for him, but then this guy wanted to hang out with me on Sundays. I would go and spend time with him – it was a relief to spend time outside of the work. When my wife came, Father Dan let us live in an extra condo that he had purchased several years before. He arranged transportation for us, and I never had to pay rent.” Often, people in Musa’s situation would have to fit in small apartments with multiple other families, but Father Dan made it possible for Musa’s family to live more comfortably. This also allowed Musa to use his income for other crucial provisions rather than all of it going for rent.

Finally, in 2012, after 5 long years of waiting, Musa’s chance came. He was told that he would be sent with his family to live in the United States.

It was the easiest time in jail because I knew we were leaving. Even so, the departure from Thailand was not easy: “It was illegal for people like us to live there as a refugee, so you had to go to court before leaving the country and confess to illegal residency. They would put you in jail for seven days and then let you go.” When asked how this last obstacle in Thailand felt, Musa just smiled and shook his head. “It was the easiest time in jail because I knew we were leaving.”

Musa and his (now) family of five arrived in Minnesota. I couldn’t quite imagine what it must have been like for Musa and his family to find themselves in a secure setting after living with so many unknowns for so long. “What was it like for you to come to America after all that you had been through?”

Musa thought for a moment before answering. “When we came, I felt like someone who was unconscious and now I am conscious. It was like opening a door, or like being born. My children will survive; they will grow. I can’t even describe it. We went from hopeless to hope—like night to day.”

In Thailand, Musa and his wife lived with perpetual worry. There was no guarantee Musa would be resettled, and he could have been arrested at any moment. His wife and children could barely bring themselves to leave the house because they were also at risk of being jailed. Musa recalled, “You ask a million questions a day because you can be arrested at any time.”

Long after the interview was over, I sat at home and tried to put myself in Musa’s shoes for a moment. Living in fear of being arrested simply for trying to survive in a foreign land was incomprehensible to me. But I did know why people like Musa go to such lengths to seek something better. After all, I myself have recently become a father, and I know that I would go to the ends of the earth to seek safety and hope of a future for my family. Looking at Musa’s story, I knew that he had simply obeyed that instinct because circumstances had forced him into making an incredibly difficult decision.

Having heard the story of Musa’s journey to the United States, I turned to the topic of Musa’s current situation in America with his family. “How do you feel about where you are now? How have you adapted to life in the US?”

I had just asked Musa about adapting to life in the U.S. and how he feels about where he and his family are now?

Musa thought for a moment and then replied, “I felt like I adjusted well, because after all the difficulties before, anything else did not seem like a big thing. I still faced hard things here, but now these things happened where I could get help.”

Musa thought for a moment and then replied, “I felt like I adjusted well, because after all the difficulties before, anything else did not seem like a big thing. I still faced hard things here, but now these things happened where I could get help.”

Musa has indeed acclimated well to life in the US. He now works as a freelance interpreter and tax preparer, while taking university classes. In his work, he assists people from various backgrounds; it is often a surprise for a client to meet a Somali interpreter who speaks Thai language! Now that he has this new life, Musa seems to do everything with a sense of joy because of the opportunity that he has been given in this new place.

At this point, I shifted the focus to the future. “When you look ahead, what do you see for yourself and your family?”

I faced a lot of hardships, and I don’t want my kids to have that. I want them to have opportunities to live their lives as Americans. “I feel like my family and I belong here. I like to think of how we can build our lives and take advantage of the opportunities that we have been given. We think about how we can express our thanks to this country,” Musa said. “I faced a lot of hardships, and I don’t want my kids to have that. I want them to have opportunities to live their lives as Americans.”

As we neared the end of the conversation, I wanted to get Musa’s insight on current events. I guessed that Musa would have a unique perspective on the hot-button issues of refugees and security. “There is a lot of talk in the media and from politicians that reflects a certain sentiment about refugees; it seems to suggest that it isn’t safe for us to bring refugees here. What are your thoughts about all this?”

Musa answered in a way that told me he had been thinking over this very thing for some time. “Sometimes I look around, and it seems like people don’t understand about each other. And it is because they don’t know each other. They have heard things, and they generalize about all immigrants, and there are stereotypes. When I was back home, I had ideas like this too. I had thoughts about America and how it was causing problems in the world. But when I met Father Dan, it changed how I felt about Americans.” …it seems like people don’t understand about each other. And it is because they don’t know each other.

While neighbors of various backgrounds may be quite different from one another, Musa believes that everyone basically has the same goals, dreams, and aspirations. He believes everyone wants to live in peace, regardless of differences of faith or culture. “People should challenge themselves to know each other. Even if I hear you are a bad man, I need to get to know you myself to see how you are before I decide,” he added.

Musa then told me that Americans are unique among all the people that he has met on his journey. They have always been helpful—ready to assist and eager to answer questions or to give of their time to help. He believes that what sets these Americans apart is that they don’t make distinctions according to where people are from.

As we spoke about this, Musa brought it back around to the topic of clans and the tribalism that he grew up with in Somalia.

“Tribalism is the most important thing in Somalia, and I blame the tribalism for our problems. The refugees are running from Somalia because of the tribalism. But I am still hopeful.”

The way Musa described tribalism gave me a picture of a tradition that largely thrives on judgment, assumptions, and insular thinking; and as we talked I recognized that there are aspects of these characteristics in the American ethos, even though our culture is not explicitly based on principles of tribalism. I found it interesting that a conversation on what to do about refugees naturally led to the topic of tribal identity. It was a direction that I was not expecting the conversation to lead.

Musa also made a connection to current events with his observations on tribalism: “We can’t just assume that ‘these people’ are my enemy, but we have to look at it from the neutral side. We need to digest and think before we judge.”

I decided to wrap up the interview with this question: “What message would you give to an American person who thought refugees should not be allowed here?”

Even if there is someone who is against me as a refugee, I want to meet them and know them, and I want them to know me. His reply was not so much a directive as it was an invitation. “Even if there is someone who is against me as a refugee, I want to meet them and know them,” he said. “And I want them to know me.”

This led me to ask him if he thought that someone like the President would take him up on such an invitation.

In response, Musa mused, “Maybe God is using Trump to prompt people to get to know refugees. They will get curious, and they will learn to love refugees.”

After the interview was over, I thought over all that Musa had said. His insight about tribalism especially hit home for me. Perhaps it is easy to imagine that in the West, we are far removed from tribal thinking, but I found that I recognized this dynamic at work all around me. It is especially obvious in these times where the middle ground is easily lost in any given debate.

It would be easy for me to take part in our cultural tribalism. For example, as someone who loves refugees, I must confess it is difficult for me to see why others might be motivated to keep out families that are seeking refuge from the horrors of war and chaos. My best guess is that the many people who support a ban on refugees are fearful for the safety of our nation. So, rather than dismissing this concern, I can acknowledge that the safety of everyday Americans is an important issue; at the same time, I can point out to anyone who supports a ban that safety and compassion are not mutually exclusive concepts. We can safely bring people like Musa and his family to the United States, as we have been doing for years; this will enrich our society even as we give new opportunities to people fleeing conflict.

All of that being said, perhaps the best way to take down walls of suspicion and fear is to take Musa’s advice to heart: we must have the courage to form a relationship with one of our refugee neighbors. I truly believe that if any American sat down and got to know someone like Musa, it would be impossible to walk away without a new friend.